Hemsby: How many other communities are at risk of erosion?

Coastal erosion claimed three homes in Hemsby last weekend and a further two properties in the village are deemed at serious risk. Are there other Hemsbys along the coast and what can be done to protect the communities which live there?

The East Anglian coastline is no stranger to coastal erosion.

During the 13th and 14th centuries the sea reclaimed much of Dunwich in Suffolk, once the 10th largest town in England.

The story of Dunwich is far from unique.

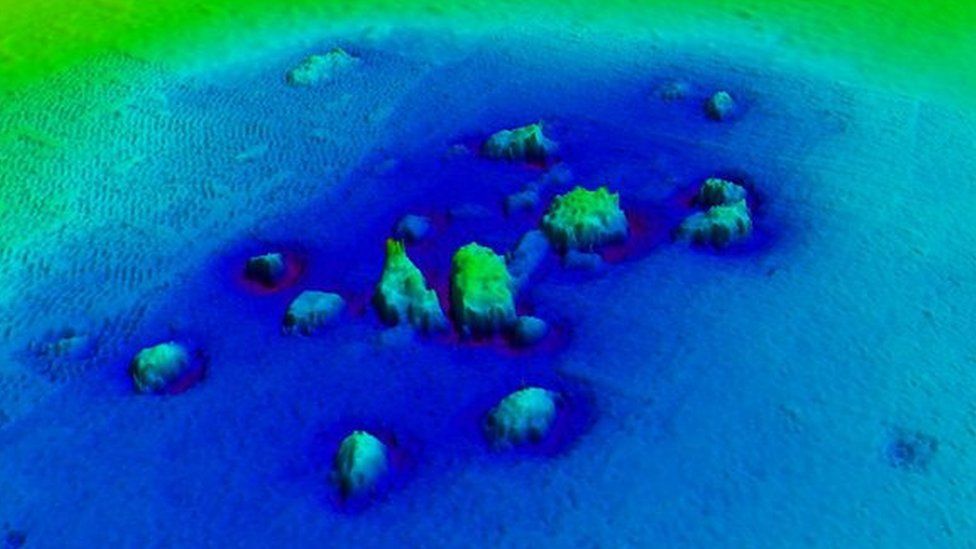

There are more than 300 settlements in the North Sea basin that have been lost in the past 900 years due to coastal erosion or flooding.

It is a threat which continues to loom over many coastal communities to this day.

Managing coastal erosion can be “eye wateringly expensive”, said Dr John Barlow, senior lecturer in applied geomorphology at the University of Sussex.

“You can’t just build a concrete wall around the entire country,” he said. “The truth is, there is a limited amount of money and it is spent using cost-benefit analysis.

“If you are looking to protect something that costs less than the cost of defending it, it won’t happen.”

It means while some areas, usually towns and larger settlements, will be protected many others will not.

Each short stretch of the East Anglian coast has its own shoreline management plan.

Together, these plans reveal the potential scale of home, business and land losses on the cards for those who live there.

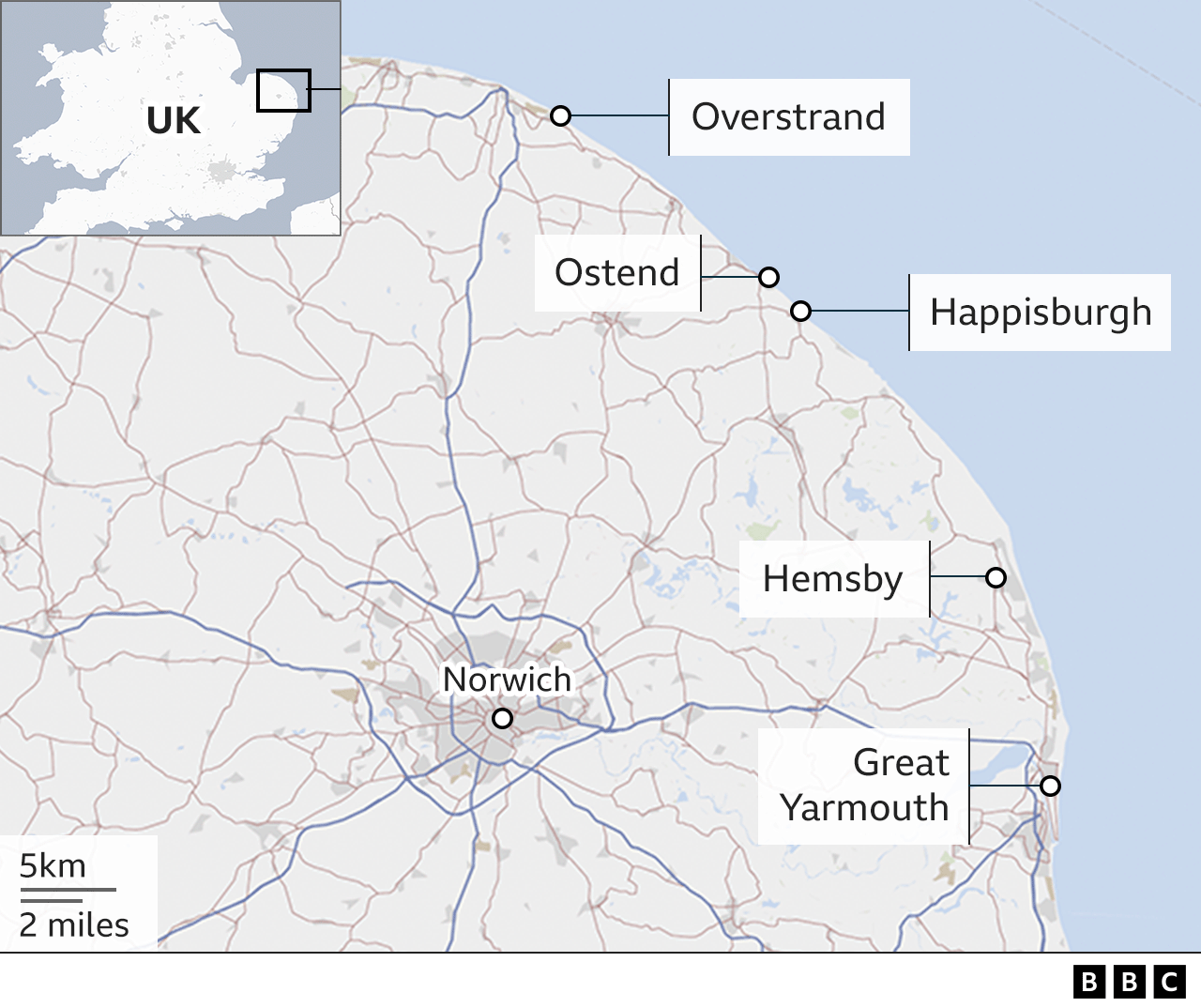

Hemsby comes under the Kelling to Lowestoft Ness plan, a document which maps out how coastal erosion might be managed along this 48 mile (77km) arc of coastline.

The plan warns how up to 90 properties could be lost between 2012 and 2025 and a further 440 by 2055.

It advises that by 2025, up to 15 properties could be lost at Happisburgh, 35 at Ostend and up to 10 between Overstrand and Mundesley.

The shoreline management plan suggests by 2105 that:

- Up to 10 houses and 10 commercial properties could be lost between Sheringham and Cromer

- A loss of between 60 and 135 houses at Overstrand

- Up to 215 houses and up to 35 commercial properties lost at Mundesley

- A loss of between 55 and 150 seafront properties in Newport and Scratby

- Between California and Caister-on-Sea a loss of between 70 and 130 seafront properties, including holiday accommodation

- A loss of up to 90 houses in Corton

Asked why East Anglia was particularly susceptible to coastal erosion, Dr Barlow said: “It’s a combination of the poorly consolidated clay, silt and sand material that form the cliffs and the exposure to storm waves coming down the North Sea.”

The National Coastal Erosion Risk Map, published in 2012, showed about 700 properties in England are vulnerable to coastal erosion by 2030 and about 2,000 could be at risk by 2060.

“It is tricky,” said Dr Barlow, “If your house is threatened by coastal erosion then it loses all value, becomes impossible to insure and you lose everything. It is a terribly difficult situation.”

The climate models predict a sea level rise of about 1m (3ft) during the coming century.

“That’s a big problem,” said Dr Barlow, “because it means the past rates of erosion are no longer going to be a good indicator for the future.”

A spokesperson for the Environment Agency said parts of England’s coast were” amongst the fastest eroding coastline in Europe”.

“Climate change, sea level rise and increased storminess will increase the rate of change which will threaten the resilience of coastal communities if no action is taken,” the spokesperson said.

“The Government is investing £5.2 billion over six years on flood and coastal erosion schemes to better protect communities across England.

“Approximately 17% (340) of the projects in the £5.2bn 2021-27 programme will help better protect coastal communities.”

What can be done to prevent or slow down the impact of coastal erosion?

There are a limited range of options.

At Hemsby, about 2,000 tonnes of rock has been brought from a stockpile at Hopton, to be placed along a 50m section of the cliff below the most vulnerable section of the access road.

“That is a priority for us,” said Karen Thomas, head of Coastal Partnerships East. “About 60 properties use that road.”

Other measures include timber revetments or seawalls to slow erosion. Such measures, however, cost millions of pounds per kilometre to install.

Elsewhere, at Happisburgh for example, there has been a process of what was once called managed retreat but local authorities now term “adaptation”.

During the last 20 years, 34 homes have crumbled into the water in Happisburgh because of coastal erosion.

North Norfolk District Council used £3.2m to purchase the most at-risk homes for a reduced price under the Pathfinder Project in 2011, helping some people move further inland.

Twelve homeowners were made an offer by the council and nine accepted.

Giving people affected time to consider their options is becoming an increasingly important aspect of how coastal erosion is managed.

Describing the situation in Hemsby, Ms Thomas said: “We feel there has definitely been an acceleration in erosion since 2018.

“The need for doing work to buy people time is where we are at.

“We are trying to do things that will allow us to work with this community so they can look at the options they have available to them.”

Hemsby resident Lance Martin moved his home 2m (6.6ft) inland, away from edge of the cliff to safety.

His property had to be raised up and laid on two connected telegraph poles. It was then rolled backwards towards safety.

“It is a race against time here but we have all gelled together. We will get through this together, ” he said.