Turkey earthquake: UK team to assess building damage

Structural and civil engineers from the UK have travelled to Turkey to help to investigate the damage caused by last month’s powerful earthquake.

They are collecting geological data and carrying out detailed assessments of why so many buildings collapsed.

Work with their Turkish colleagues has revealed examples of poor construction, including large pebbles mixed in concrete, which weakens its strength.

But the sheer power of the quake also caused some of the devastation.

The ground movement was so great in some areas that it exceeded what buildings had been designed to withstand.

Turkey is also carrying out its own extensive investigations into the quake.

The research is being carried out by the Earthquake Engineering Field Investigation Team (EEFIT).

The group includes experts from industry as well as leading academics and has carried out assessments of major earthquakes over the last three decades.

They will combine their findings with research being carried out by Turkish teams and other structural engineers with the aim of learning lessons from the earthquake and finding ways to improve the construction of buildings to make them more resilient.

“It’s important to get the full picture rather than just looking at a snapshot of a single asset or a single building,” explains Professor Emily So, director of the Cambridge University Centre for Risk in the Built Environment, who is co-leader of the investigation.

“The successes of the buildings that are still intact and perform perfectly well are as important as the neighbouring buildings that have collapsed.

“And actually having that distribution, having that overview, is really key to what we can learn from this earthquake.”

The Magnitude 7.8 earthquake struck on 6 February in southern Turkey close to the Syrian border and was followed by powerful aftershocks.

More than 50,000 people lost their lives in the region as buildings collapsed.

In the wake of the devastation, there has been scrutiny of building regulations and construction practices in Turkey. Now the EEFIT team is carrying out technical evaluations of the performance of buildings in the area.

Structural engineers from Turkey, who are working with the team, have already found some problems.

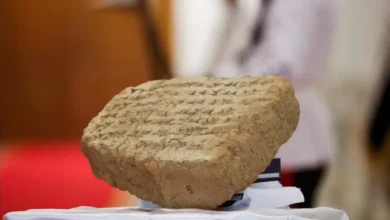

Samples of concrete taken from a collapsed building in Adiyaman have revealed that it contains 6cm-long stones. They have come from a nearby river and have been used to bulk out the concrete.

“That has some serious implications on the strength of the concrete,” says Prof So.

And steel bars inside the concrete, which should reinforce it, have been found to be smooth instead of ridged.

This means the concrete doesn’t cling to them, again weakening the structure.

In Turkey, many older buildings collapsed during the quake, but some modern ones also failed.

New building codes were brought in after a major earthquake in Iznit in 1999, and Prof So says newer buildings should have fared better.

“I think it’s really important that we recognise those and actually do the testing, to find out why these new buildings, which would have been built to code, have failed in such a way,” she told BBC News.

The EEFIT team is also analysing the nature of the quake.

Dr Yasemin Didem Aktas, co-leader of the expedition, from UCL in London, said that the earthquake was extremely powerful.

“Even the aftershocks were as large in magnitude as a decent-sized earthquake,” she said.

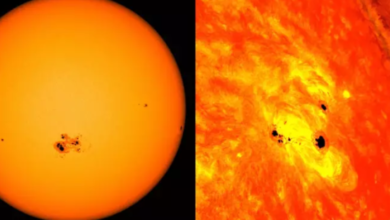

The quake also caused major ground shifts.

“In an earthquake, the ground shakes in a horizontal and vertical fashion. Often the vertical component is much lower and negligible compared to the horizontal movement. However, this event recorded very high vertical accelerations as well.”

Some areas saw a process called liquefaction. It turns the solid ground into a heavy fluid – like very wet sand – a tell-tale sign of this is a building that has toppled over or has sunk.

“I think the characteristics of the events also played a very important role in the devastation that we are seeing,” Dr Aktas added.

But buildings can be designed to be earthquake resilient.

Ziggy Lubkowski, who leads the seismic team at design and engineering company Arup, which has sent engineers to Turkey for the investigation, said: “What we try and do when we design buildings is to prevent life loss.

“The basic design principle is to allow some form of damage within the building. That damage absorbs the energy of the earthquake, and ensures that the building still stays upright, but doesn’t collapse.”

Components such as dampers, which act like shock absorbers as the building sways to and fro, and rubber bearings, which are fitted underneath a building and absorb the energy of a quake, can be added.

But all of this costs money.

“Those increases, in terms of the structural cost of the building, may be in the order of 10 to 15%, depending on the nature of the building,” Ziggy Lubkowski says.

“But actually, if you think about it, the fit-out costs of a building often outweigh the structural costs of a building. So at the end of the day, the additional structural costs are not that much more.”

The United Nations has estimated that the cost of clearing and rebuilding in the earthquake in Turkey could exceed $100 billion.

The EEFIT team says the findings, which will be published in the coming weeks, could help in setting new building codes to stop the devastation caused by this earthquake from happening again.