Shackleton’s Endurance: The book that records all disasters at sea

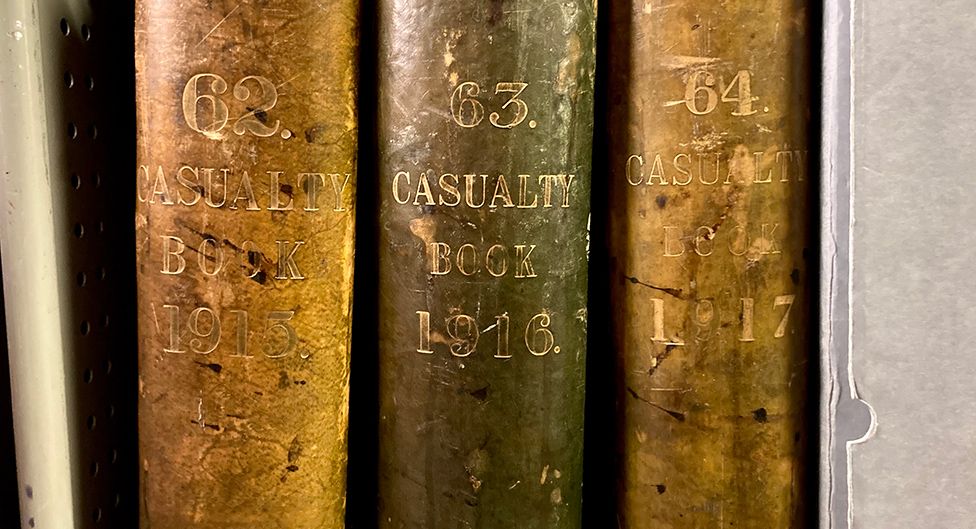

It’s a hefty, leather-bound tome that records the sunken and the missing.

You can see it on the famous underwriting floor of Lloyd’s of London, the insurance market. They call it the Casualty Book.

I’m here in the spectacular Richard Rogers-designed building to track down information on one wreck in particular – that of Sir Ernest Shackleton’s Endurance. This week marks a year since its discovery in the Antarctic.

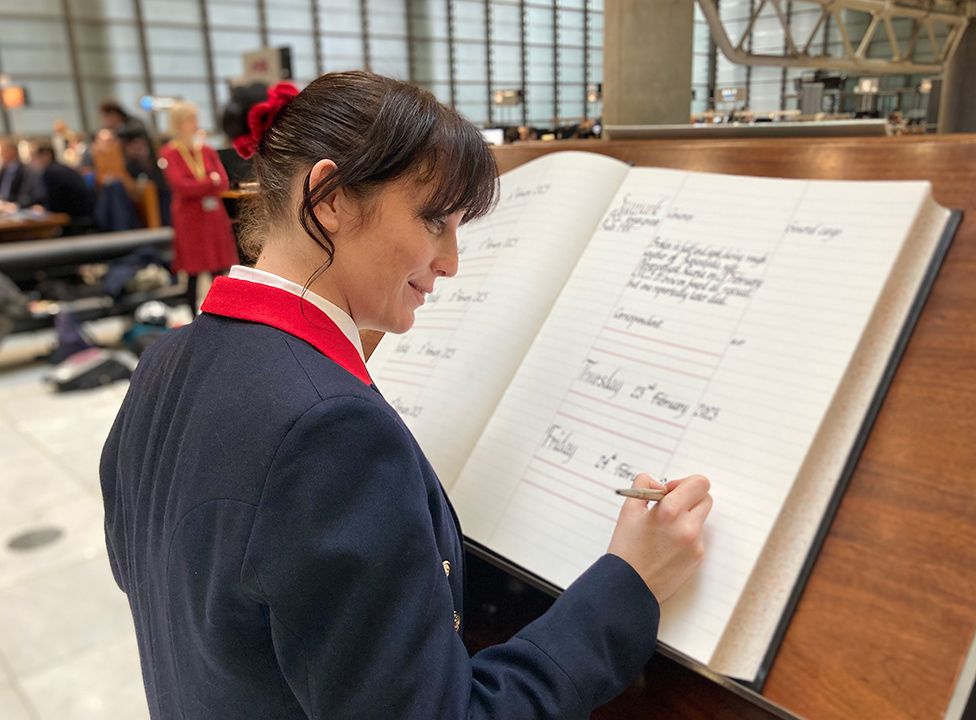

Every few days, after a maritime incident, a “waiter” – one of the market’s uniformed clerks – will approach the lectern on which the Casualty Book stands to make an addition.

Today, this job falls to Zsofia Korodi. With dipping pen and ink, she’s entering the details of a recently lost cargo ship.

It demands an ornate script that has hardly changed in 250 years.

I’m hoping I can find a reference somewhere to Shackleton’s doomed vessel.

The story of the Endurance has captivated the world for decades.

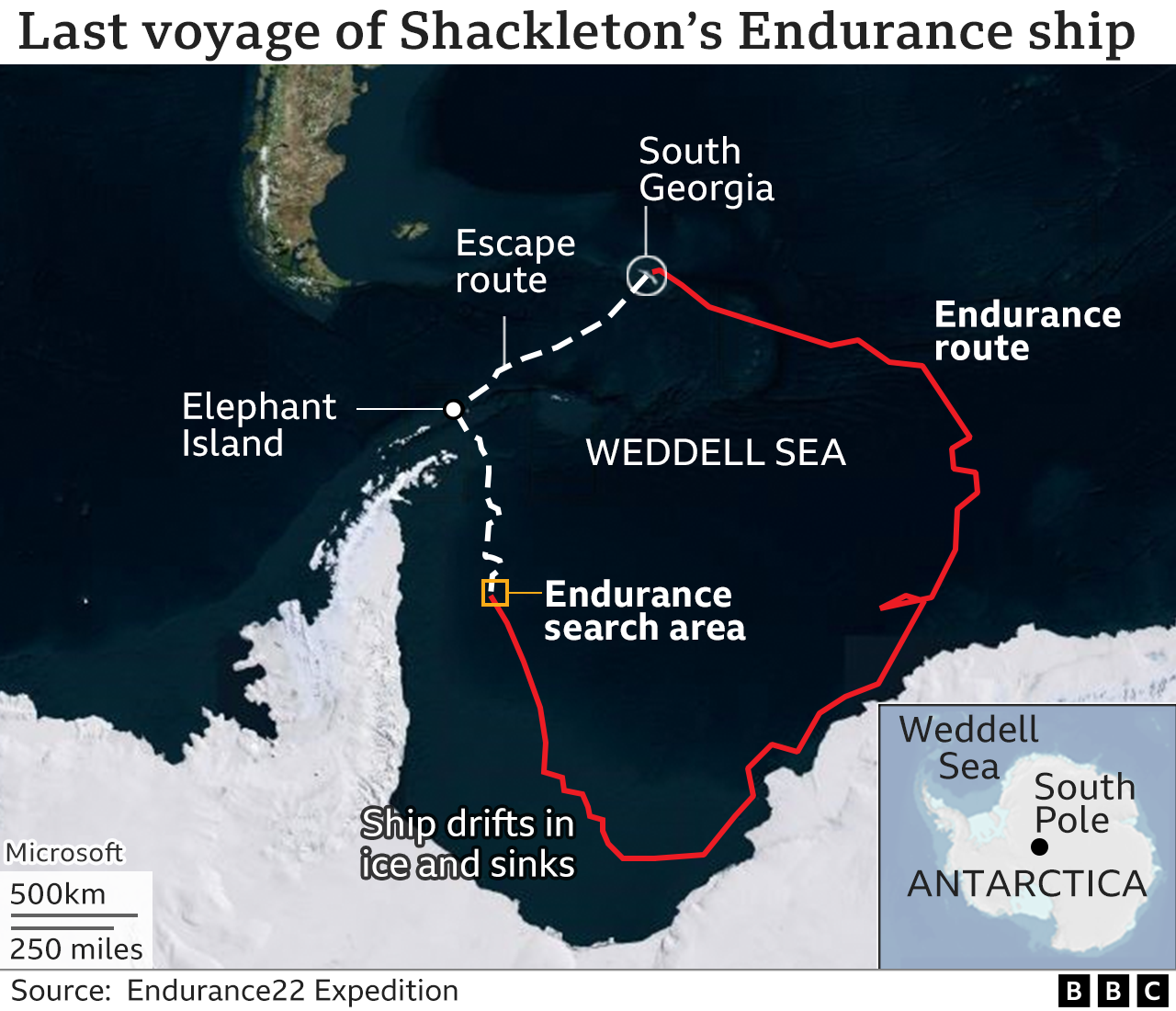

It was taken in 1914 by the British/Irish explorer to the Antarctic, where it became trapped and punctured by ice.

As it dropped 3,000m to the floor of the Weddell Sea, Shackleton and his crew made what still seems an impossible escape to safety.

Almost as extraordinary was the polar yacht’s discovery on the ocean bed this time last year. It had been regarded as perhaps the single most difficult wreck to find anywhere on the globe.

Endurance was insured by Lloyd’s for £15,000, on a premium of £665. Indeed, it was the very first vessel to enter Antarctica’s “ice zone” to carry a policy from the London market.

So, where is the record of its loss?

All the old Casualty Books – one for each year – are archived in the capital’s Guildhall Library, but if you ask to see the one from 1915 (Endurance sank on 21 November, 1915) you won’t find the entry.

You actually have to pull out the 1916 volume and go to June of that year to find the record.

The discrepancy is the result of the time delay in getting news of the sinking back to the UK.

It took months for Shackleton to reach a place where he could raise the alarm and telegraph London.

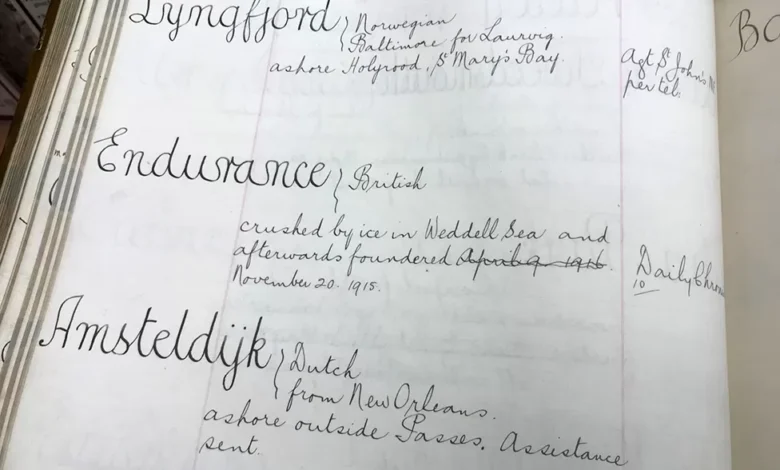

The entry reads: Endurance | British. Crushed by ice in Weddell Sea and afterwards foundered

There’s a reference to the Daily Chronicle newspaper, which had the exclusive reporting rights on Shackleton’s adventures and which the Lloyd’s waiter at the time must have used as the source.

What’s fascinating is that the entry contains a number of errors.

“When you look at the record, they get the date wrong for the sinking, and they have to scribble it out; and then they put in another date, and that’s wrong too,” chuckles Dr John Shears, who led last year’s Endurance22 expedition that finally identified the location of the wreck.

Those errors are probably the result of some misinterpretations of telegrams and even mistakes by Shackleton himself as he communicated with the Chronicle.

The matter of insurance is very significant because it affects who might be the owner of the wreck to this day and what might happen to it in the future.

When underwriters determine a total loss, they can take ownership of a vessel, even if it’s at the bottom of the ocean. Almost invariably, they refuse; certainly in modern times. No-one wants to be responsible for a wreck that could later cause pollution.

“I’ve seen it done so theatrically,” said Stephen Harris who’s worked in and around Lloyd’s for almost 50 years.

“The broker will go up to the underwriter to offer them the ship, which by law they must do, and the underwriter will make sure he’s grandstanding, and in a loud voice will announce ‘I decline abandonment’ so everyone hears. In that case, even though the ship owners got the full insurance value, they retain ownership.”

The renowned shipwreck hunter David Mearns, who has researched the history of Endurance, has established this was the case with Shackleton’s vessel, too.

This means ownership in 2023 rests with the explorer’s descendants – his granddaughter Alexandra (Zaz) and grandson Nicholas.

And they are very determined that – as owners – the wreck should not be disturbed.

“Nobody’s going to rummage in her,” Alexandra said. “I’m very happy for photographs to be taken, but no rummaging, no touching. Just leave her as she is.”

Endurance already has some protection under the Antarctic Treaty. The fallen timbers have been declared a Historic Site and Monument.

But further measures are being pursued under the leadership of the UK Antarctic Heritage Trust (UKAHT).

The spectre here is the Titanic, which has essentially become a tourist destination. Thousand of items from the doomed cruise liner have been brought to the surface.

The UKAHT hopes to get the agreement of Antarctic Treaty signatories to impose strict protocols to prevent anything similar happening with Endurance.

“The starting point for any decisions about control has to reflect the situation that the wreck is owned by somebody,” said David Mearns. “It’s not that Zaz is necessarily opposed to what might be decided but she has to have a seat at the table.”