Blue Jean: The lesbian teachers who inspired film about Section 28

Bafta-nominated Blue Jean follows a lesbian PE teacher in the late 1980s at the time when a controversial law banned the “promotion of homosexuality” in schools. Two women who inspired the film recall the impact of Section 28 on them.

Coming face-to-face with a younger version of yourself must be a very strange experience. Especially if that younger self is going through one of the most difficult periods of your life.

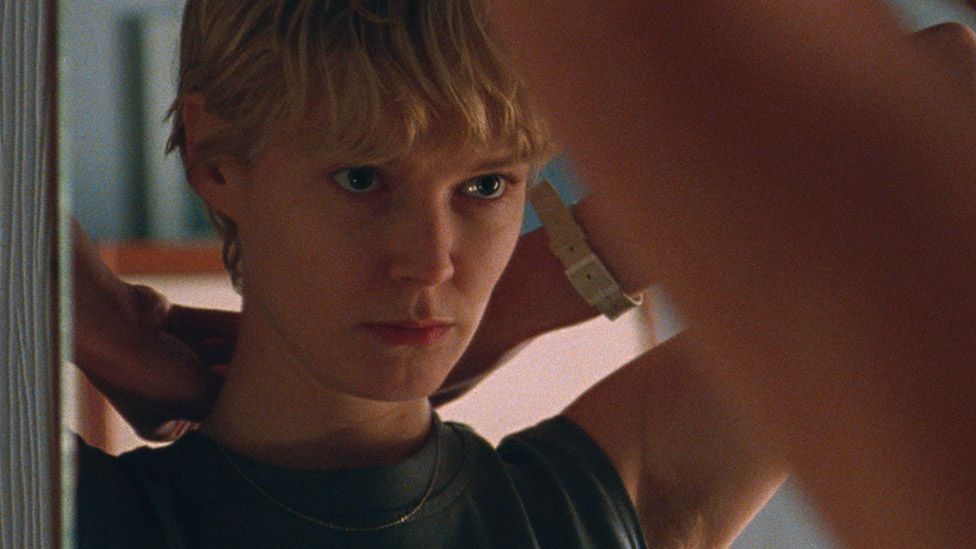

That was how Catherine Lee felt as she watched a PE teacher in her 20s, her short blonde hair uncannily similar to her own, taking netball practice in a high school sports hall.

“It was just like the gym I used to teach in every day,” Lee says.

She experienced this surreal sort of time travel by visiting the set of Blue Jean, a new British film shot in Newcastle and set in the late ’80s, which is partly inspired by her story and those of other gay teachers.

From behind the cameras, Lee watched as the actress playing the young teacher intervened when the lesson descended into taunts, and a homophobic slur was shouted.

“I hadn’t heard that word for so many years, and my reaction… it was almost visceral,” Lee says. “It took all my restraint to not put my fingers in my ears.

“Emotionally, I was affected far more than I expected to be.”

In the film, Jean, played by Rosy McEwen, must navigate a tricky web of relationships at school and in her private life, at a time when public and political attitudes to homosexuality made it a fierce moral battleground.

Introduced in 1988, Section 28 was designed to safeguard traditional family values and protect children, according to supporters. Opponents called it “state-sponsored homophobia”.

For many gay teachers, it meant not just avoiding references to sexuality in lessons, but fearing for their jobs if they came out, or supported students who were struggling with their own sexuality, or confronted homophobic bullying. For gay teenagers, it fuelled that bullying and a sense of shame.

Lee, a PE teacher in Liverpool at the time, told McEwen about her experiences.

“We spoke at length about what it was like to be permanently anxious at school, never in the moment, always thinking two steps ahead in case somebody was going to ask you what you did at the weekend, or ask you to go to the pub, and cross the professional into the personal.

“Seeing Rosy as Jean embody that, and be so small and anxious and timid in those school scenes – it affected me really profoundly,” continues Lee.

“I went from feeling sorry for her and wanting to put my arm around her and tell her that it would all be OK, to wanting to shake her and feeling really angry with her for not being bolder.”

Lee is now a professor at Anglia Ruskin University and has just published Pretended: Schools and Section 28, drawing on her diaries from the time.

Sarah Squires, who taught in Exeter and London, also advised the film’s makers. Section 28 contributed to “internalised homophobia” that she is still processing today, she says.

When she visited the set, Squires was shown a clip of Jean and other teachers in the staff room watching a news report about a Section 28 debate in the Houses of Parliament.

McEwen “conveys this absolute turmoil, this inner struggle, so brilliantly”, Squires says. “I was absolutely in tears just watching that piece of footage. It just hit me right here in the solar plexus.

“They’ve managed to capture the constant inner turmoil. You were constantly vigilant, always having to present this almost two-dimensional version of yourself because you’re checking yourself. You’re constantly on guard and need to make sure what you’re saying doesn’t give you away. So you’re undercover the whole time.”

The film is up for the best debut award at next week’s Baftas, and recently won four British Independent Film Awards including best lead performance for McEwen.

“When I finally saw Rosy convey this person, I had to just find her and thank her and I hugged her, and it felt a bit like hugging my former self for getting through it somehow,” adds Squires, now a principal lecturer at Leeds Beckett University.

“It was quite a triggering experience and a very interesting reaction.”

Self-censorship

Section 28 stopped councils and schools “promoting the teaching of the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship”.

It was in force until 2000 in Scotland and 2003 in England and Wales. Paul Baker, author of Outrageous!: The Story of Section 28 and Britain’s Battle for LGBT Education, says he is not aware of any successful prosecutions.

“I think people did lose their jobs over it, but often it wasn’t put down explicitly to Section 28,” he says.

“There was a lot of self-censorship. People were so scared of losing their jobs, or getting into the newspapers, that they just kept quiet. They didn’t use certain books in English literature classes and things like that. If there was bullying, they turned a blind eye to it.

“I have had teachers write to me, saying how terrible they now feel about things they let slide or didn’t confront.”

Georgia Oakley went to school in the late ’90s and early 2000s, but only became aware of Section 28 when she came across articles about it later.

“Immediately, I started thinking about what effect this law must have had on my life without my even knowing that it had existed,” she says.

“I was also simultaneously thinking about what it must have been like for a queer teacher at that time, and the domino effect on anyone that was a student.”

Now 34 and a film-maker, Oakley decided that story should be told. She has written and directed Blue Jean.

She thinks Section 28, along with wider prejudices, had the effect of stopping many people being open about their sexuality.

“My experience of growing up was that there was just a complete absence of queer role models,” she says.

“I wasn’t aware of anybody in my life or the public eye, particularly when we’re speaking about women. I wasn’t aware of any lesbians in my life – in my school, within my teachers, within my parents’ friends – which actually of course was not true.”

This year is the 20th anniversary of the end of Section 28. With its 1980s setting, Blue Jean is an evocative period piece.

There are, though, parallels with laws that have recently been introduced in Florida, Russia and Hungary.

“I suppose one message that I hope is communicated is that we can never get complacent about our rights because everything is delicate,” Oakley says. And while much is now different, some things are not, she says.

“There’s a whole load of Jean’s experience that is still relevant now. And not just relevant, but things that I experience all the time. Little micro aggressions. In that respect, not much has changed.”

Blue Jean is in UK cinemas from Friday.