Europe’s mission to Jupiter’s icy moons ready for launch

Europe is about to undertake one of its grandest ever space missions, to explore the icy moons of Jupiter.

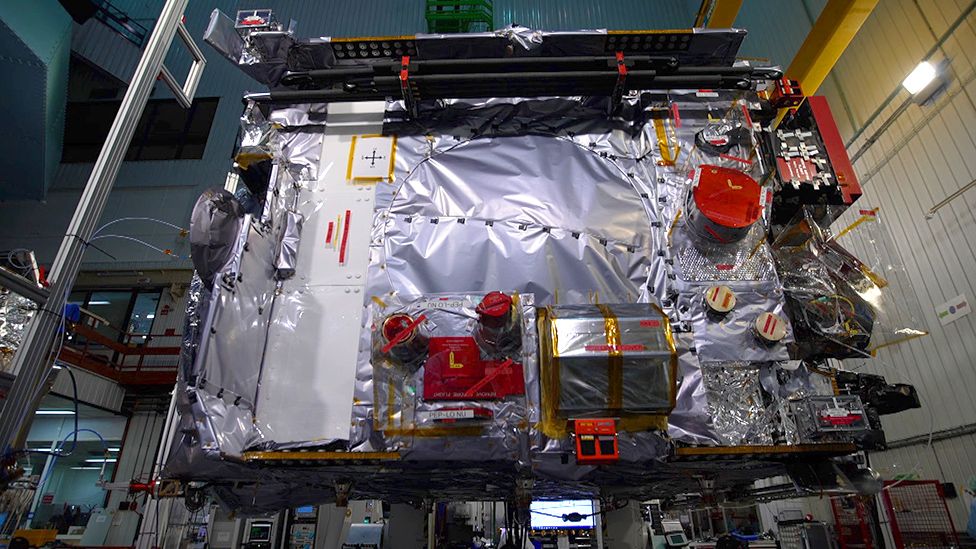

The Juice satellite is going through final testing in Toulouse, France, after which it will be shipped to the launch site in South America.

It’s due to depart Earth in April.

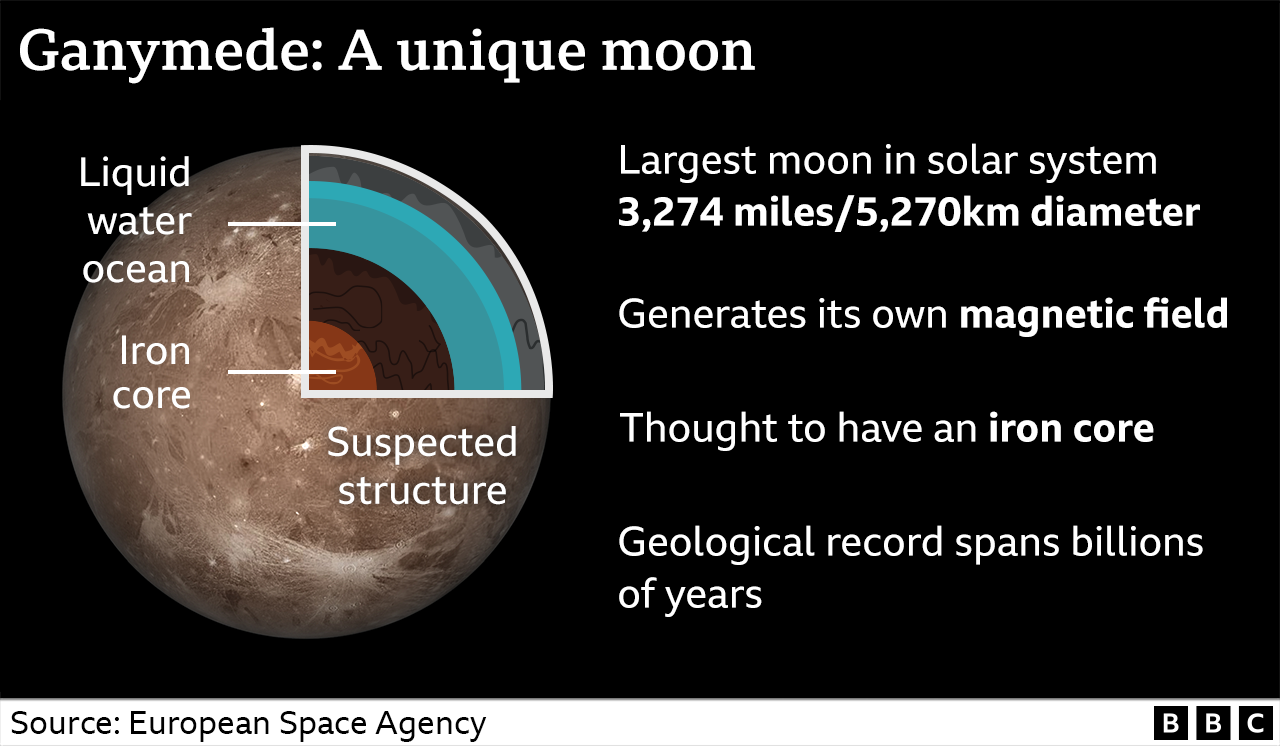

The six-tonne spacecraft will make a series of flybys of Callisto, Ganymede and Europa, using an advanced package of instruments to investigate whether any of these worlds are habitable.

This might sound fanciful. The Jovian system is in the cold, outer reaches of the Solar System, far from the Sun and receiving just one twenty-fifth of the light falling on Earth.

But the gravitational squeezing and pushing the giant planet gives its moons means they have the energy and warmth to retain vast quantities of liquid water at depth. And we know on Earth that wherever there is water, there’s an opening for life.

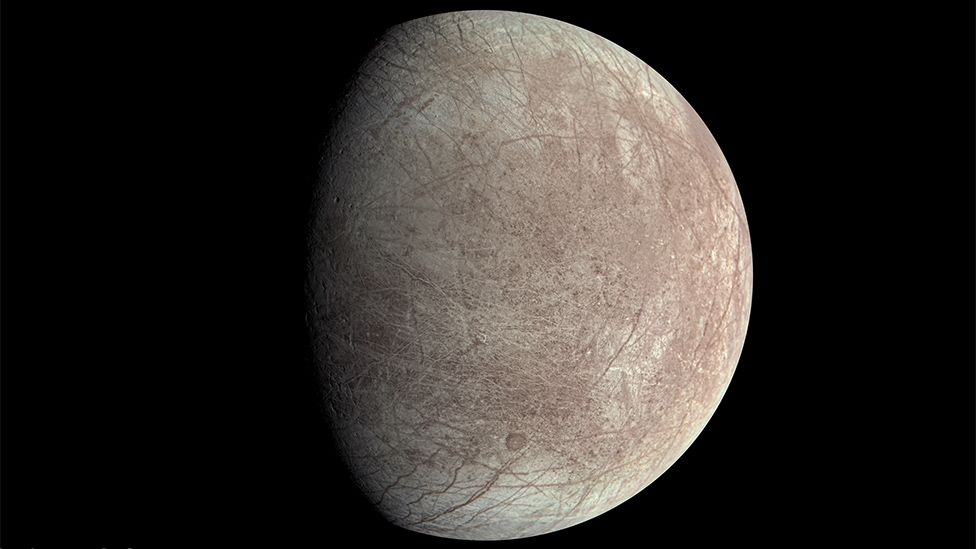

“In the case of Europa, it’s thought there’s a deep ocean, maybe 100km deep, underneath its ice crust,” said mission scientist Prof Emma Bunce from Leicester University, UK.

“That depth of ocean is 10 times that of the deepest ocean on Earth, and the ocean is in contact, we think, with a rocky floor. So that provides a scenario where there is mixing and some interesting chemistry,” the researcher told BBC News.

It’s a 6.6 billion km journey lasting 8.5 years.

Mark the calendar for July 2031. That’s when Juice arrives at Jupiter. It will then conduct 35 flybys of the three moons before settling permanently around Ganymede in late 2034.

The European Space Agency (Esa) project team behind Juice held a major review this week and concluded the mission was “go for launch”.

Aerospace company Airbus has spearheaded the construction of the €1.6bn (£1.4bn; $1.7bn) JUpiter ICy moons Explorer.

The manufacturer has pulled in expertise and components from all across the continent.

Everything is now fully assembled, including Juice’s suite of 10 scientific instruments.

“We have a number of high-resolution cameras on this probe in all possible wavelengths – in infrared, the visible and ultraviolet,” explained engineer Cyril Cavel, as he pointed out a collection of boxes hanging off one side of the silver and black satellite.

“You can see all these instruments underneath protective, transparent covers. The high-resolution visible telescope, which is called Janus, will take fantastic pictures very close to the moons because we will do flybys at just 400km altitude. They will be stunning shots,” the Airbus Juice project manager said.

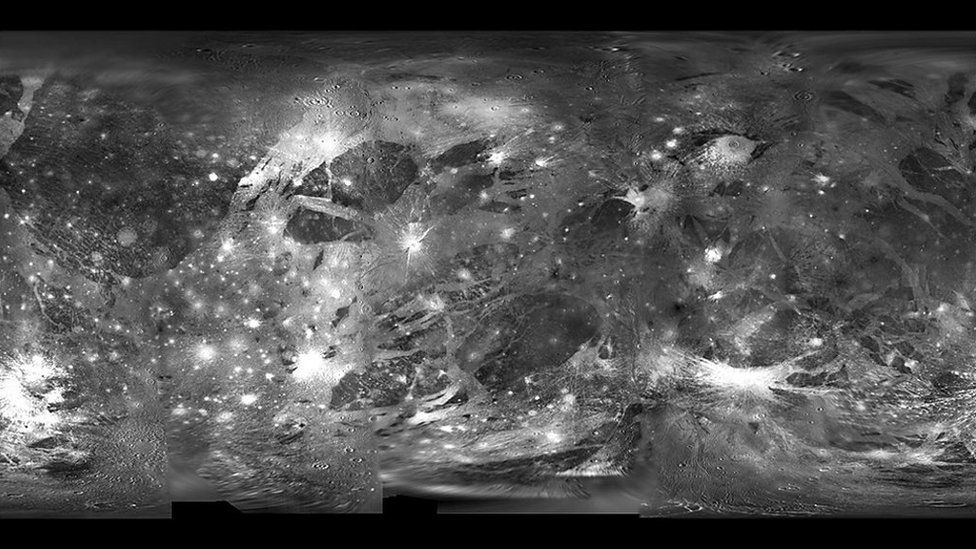

Radar will also peer inside the moons; lidar – a laser measurement system – will make 3D maps of their surfaces; magnetometers will trace their complex electrical and magnetic environments; and sensors will sample the particles that whiz around them.

Juice won’t be searching for specific “biomarkers”; it won’t be trying to detect alien fish in the deep oceans. Its job is to learn more about the possibilities for habitability that future missions could then investigate in more detail. Scientists have long pondered the idea of putting landers on one of Jupiter’s icy moons to drill through its crust to the water below.

That could happen one day, perhaps; in the latter half of this century.

You need patience to work in the outer Solar System. The orbits of Earth and Jupiter may be “only” 600 million km apart, but you can’t easily go direct, not without a stupendous rocket. And even though Europe’s Ariane 5 is powerful, it doesn’t have that kind of heft.

Instead, it will send Juice on a rather circuitous route that will use the gravity of Venus and Earth to slingshot the probe out to the gas giant.

Juice is built a little like an air-conditioned tank.

Unprotected, its electronics would rapidly degrade in the harsh radiation that swirls around Jupiter. And that long journey inwards towards Venus and then out to the gas giant will see temperatures on the exterior of the satellite swing from 250C to minus-230C.

“We have two big vaults inside the spacecraft to protect the computers from radiation and to maintain them through a network of pipes at the same level of temperature,” said thermal architect Séverine Deschamps.

“The same is true for the propulsion system. Its operation has to be maintained around the 20C, quite warm, to get a good level of performance when firing.”

Juice won’t be alone in its work.

The US space agency Nasa is sending its own satellite called Clipper.

Although it will leave Earth after Juice, it should actually arrive just before its European sibling. It will focus on Europa.

Together, the two satellites will make a powerful team.

“You get a much deeper understanding having the two there together, and it removes some of the guesswork as to what’s going on,” said Prof Michelle Dougherty, the principal investigator on Juice’s magnetometer instrument.

“It will be interesting, for example, when Clipper is going past Europa if there is a plume coming from the moon. Clipper will be making the close-in measurements, but Juice will be watching at a distance to see what impact that has on the environment around Europa and whether we get bigger spots in the auroral lights on Jupiter.”