Sierra Madre: Fighting to save what’s left of a vital rainforest

Francisco Elle is haunted by the faces of children he could not save.

It’s what drives him deep into the dense rainforests of the vast Sierra Madre mountain range day after day, carrying a heavy wicker bag full of fresh saplings on his shoulders.

His lean figure ducks under a thick ceiling of leaves. Even with his glasses falling to the end of his nose, he manages to avoid being tripped by exposed tree roots as he hurries along a faint trail to his latest tree planting site.

Following him is tough going, especially as clouds roll down the hillside brushing the tips of the branches with a fresh mist of rain.

He once made a living chopping down these trees which had taken centuries to grow. Now in his 50s, he has turned from illegal logger to forest ranger after witnessing what he describes as “nature’s revenge”.

More than 1,000 people were killed when Francisco’s village, along with several others, was washed away by a landslide in December 2004.

“I saw lifeless children all lined up on the street while the houses were all destroyed. There weren’t any houses left, even ours was gone. When I remember the things we did, I feel helpless,” he said during one of the few breaks he was willing to take that day.

Does he feel guilty about his past?

He turns away in tears. After several minutes, he answers: “I blame myself. Maybe if I didn’t cut trees, maybe it wouldn’t have happened.”

Saving the Sierra Madre

The Sierra Madre, Filipinos will tell you, is the backbone of Luzon, the main island of the country. Some even describe the mountain as their mother and protector. Stretching for more than 500km (310 miles) from north to south, her uneven, rugged peaks are thought to shield the 64 million people who live there, including those in the capital Manila, from the worst of the strong typhoons which barrel in from the Pacific Ocean.

But 90% of the original rainforest is now gone. Illegal logging, mining and quarrying have taken a toll. And without the tree roots for stability and the vast canopies of the forest to absorb the heavy rains, landslides and flash floods are becoming more common, especially as the frequency and the severity of the storms increase.

“People say illegal logging is destroying nature, but God gave all this to us so we can use it,” says Marc. He is in his mid-50s and makes a living illegally cutting down wood for housing and other construction projects.

He shows off a chainsaw that he bought after selling his cow seven years ago. It’s a prized possession because chainsaws are registered here – just like guns.

Marc says the authorities will only “catch him when he is dead”. He and his wife Grace live deep in the forest in a small woven bamboo hut with a corrugated iron roof which seems to defy gravity. It is built on a sloping hillside surrounded by coconut trees.

Their last big order was in March. It took around a month to complete with the help of others and earned them around $300 (£250), which amounts to 16,500 pesos. The orders come from a middle man. But getting the wood to them is a difficult process.

“We wait until midnight because we are hiding from the soldiers and forest rangers. We will get paid a week after that.

Despite the risk, logging is the only source of income for some of the poorest Filipinos.

“My message to people is to not get angry at us because we don’t actually want to do this,” Marc says. “We can only get our money for basic necessities from farming our land. Others can afford to get mad because they have other sources of livelihood but for us, we have none.”

But Francisco says that doesn’t change the fact that they still have to face the devastating impact of logging.

“We did not know what we were doing, we just cared about getting money for our food every day because there were no other sources of livelihood. We would dig even the roots of the trees we cut. We would cut down all the trees in an area of the forest until there were no large trees left.”

Now, he believes, chopping down “just one piece of wood… is one of the greatest sins against nature”.

Near a flowing stream, he lays down his heavy bag of saplings and directs an army of volunteers working for the Haribon Foundation – a dozen men and women carrying bags of saplings that weigh up to 15kg. Some are wearing flip flops, but they are still sure-footed as they clamber up the steep bank through cloying mud.

Under the rainforest canopy, Francisco vows to keep working to ensure “history will not repeat itself”.

“Our enemy now is flash flooding,” he says. “Even my children, I teach them to plant trees, I tell them not to follow those who do logging.”

The clouds dip a little lower and the first drops of rain splash down onto the leaves. The volunteers continue to plant, unfazed.

The saplings are narra trees – the fast-growing national tree of the Philippines.

In 10 years, they hope this part of the forest will be green again.

A deadly job in a deadly conflict

Replanting trees in the Sierra Madre is a long, difficult and even dangerous job.

Like rainforests everywhere, this one too is home to a conflict between those desperate to make a living and those desperate to preserve life. And the risk of that conflict becoming deadly is high.

A Global Witness report identified the Philippines as one of the most dangerous places in the world to be an environmental or land rights activist.

“Once, we called out to someone to tell them to stop cutting trees. They told us that they might kill us,” Francisco says.

“I told them that we weren’t there to pick a fight and we were just explaining what will happen to all of us if they continue what they do. I said ‘you won’t be the only one affected, it’s all of us’.” He says they had a frank discussion and peacefully went their separate ways.

But that’s not always the outcome.

At least 270 people have been killed in the last 10 years defending these rainforests. Two forest rangers who work for the Masungi Georeserve in the south of the Sierra Madre mountain range were shot and wounded in 2021, which prompted the reserve to call for urgent protection for their staff.

The Department of Environment and National Resources has also made calls over the last few years for their forest rangers to be armed.

But rangers are not the only ones vulnerable to attacks by armed illegal loggers – 114 of the environmental activists killed in the Philippines were from indigenous communities.

The Philippines is losing around 47,000 hectares of rainforest each year, according to the Forest Management Bureau of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources. That’s an area around the size of 87,700 football fields. It is also thought to have the highest number of threatened species in the world.

The majority is lost to logging, but the battle isn’t just over timber.

Climate change v growth

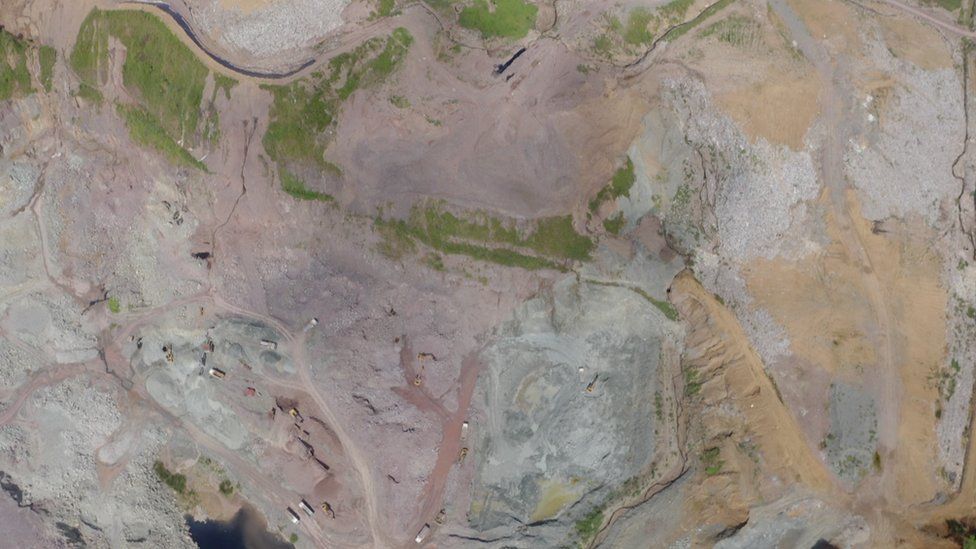

This vast mountain range is also rich in copper, gold, nickel, chromite and limestone. And that is big business in a developing country keen to rebuild its economy after being battered for nearly three years by the pandemic.

There was a moratorium on new open-pit mining projects until 2021, but several companies have long-standing permits to use nearby land.

“We need a comprehensive review of all the permits given for mining,” says Tony La Vina, associate director for climate policy and international relations at the Manila Observatory.

“There are well-documented links between politicians and mining companies in the Philippines. Logging and mining have fuelled the political careers of many local and national politicians. That link has to be broken.”

Getting a true picture of the scale of mining projects along the Sierra Madre mountain range which spans 10 provinces is difficult. The BBC contacted local officials in each province to find out how many permits they had issued in the last five years.

Only those in one province, Rizal, responded. They said that they had issued three permits for “mineral extraction”, but that the land owners had “prior rights” which allowed them to also mine in the protected area.

The Department of Environment and National Resources, which issues mining or quarrying permits, is also yet to respond to the BBC’s request for a comment.

To complicate matters further, the same department employs hundreds of forest rangers to protect the Sierra Madre.

It captures the contradiction developing countries face in their fight against climate change. Their growing populations need houses, roads and jobs. But the infrastructure and industries that provide those are often also responsible for the deforestation and flooding that threaten their future.

These countries are hoping richer nations will help. The Democratic Republic of the Congo, Indonesia and Brazil, home to 52% of the world’s rainforests, announced that they will work together to secure “payments to reduce deforestation”.

The Philippines has turned to China to help fund a huge dam to meet the rising demand for water in Metro Manila, Rizal and Quezon. Officials argue the benefits of the project outweigh the disruption to the environment. But others fear it will further erode precious flora and fauna, and pave the way for other developments.

When severe storms threaten Luzon, the priorities change – quickly. In September, as super typhoon Noru made landfall in the Philippines, #SaveSierraMadre trended on Twitter. TV Networks were filled with pundits who praised the forest for protecting the island.

“We can’t just have one use for the Sierra Madre, but we have to prioritise,” Mr La Vina says. “We should not develop infrastructure that will kill or defeat all the other uses of the Sierra Madre. The stakes are much higher now.”

The competition for resources in the Sierra Madre comes at a time when the country might need their mother mountain’s protection more than ever. The Philippines is one of the most disaster-prone countries in the world – and now, it is also one of those most vulnerable to climate change.

Mr La Vina is hopeful: “I know there are many out there working hard to protect our forests. And awareness is growing. If we keep moving forward, we have a greater chance now of success than ever before.”

But that’s not a feeling shared by those who are on the frontlines.

Mother Mila Llagas lives next door to a quarry in Rizal that is under investigation after her neighbourhood of scattered bamboo huts along a river was submerged by a flood. She now keeps her prized possessions in a bag, along with essentials for her and her children.

“I was born here – those mountains there above, they were okay, we didn’t experience flooding back then,” she says, pointing to the steep mountainside above the river. Some of her neighbourhood has been sliced away and is no longer green with trees. Instead it is a grey stone quarry.

Now, she adds, there are not trees to absorb the rains and “nothing” to stop the river when it swells.

“Everyone is wary of the future. We can’t do anything, we don’t have any power to stop those things.”